The Civic Society column with David Winpenny

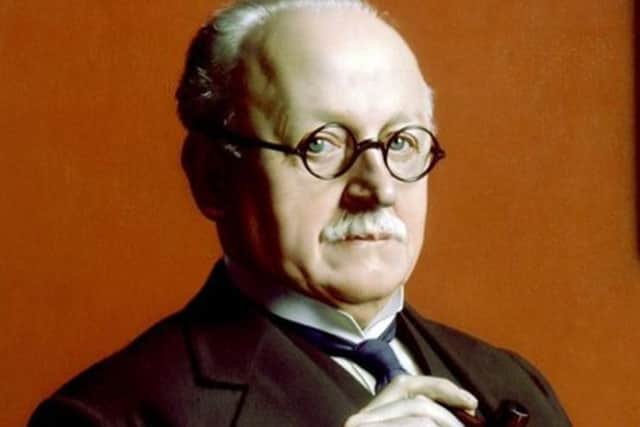

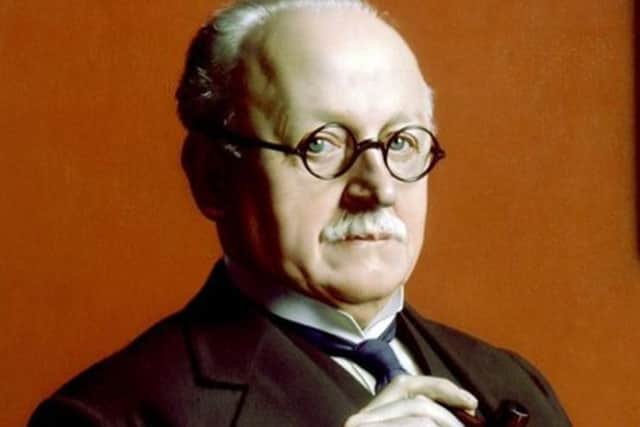

They approached the most famous English architect of the time, Sir Edwin Lutyens, to recommend a fitting memorial that could be placed in cemeteries throughout the theatre of war.

Lutyens recognised the need for something elemental rather than elaborate.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTaking an idea put forward by Rudyard Kipling, he designed a rectangular, altar-like block of stone: he described it as ‘one great fair stone of fine proportions, lying raised upon three steps, of which the first and third shall be twice the width of the second’.

Each stone is 11 feet long and almost five feet high.

The Imperial War Graves Commission immediately accepted the design, and when the war finished what came rapidly to be known as the ‘Stone of Remembrance’ began to appear throughout Europe and in many of the countries that had sent troops to fight in the conflict.

It was placed where there were 1,000 or more graves of the fallen or at memorial sites commemorating more than 1000 war dead.

By 1937 there were 560 Stones of Remembrance in France and Belgium alone; the use of the Stone of Remembrance was continued by what became the Commonwealth War Graves Commission for World War II cemeteries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

This was the first time such a national – even international – way of commemorating the dead of a war had been organised – though, of course, this was the first such all-enveloping conflict. Earlier wars had been marked by monuments, too, but they tended to be one-off structures and of more local significance.

In the Middle Ages crosses were sometimes placed on the site of battles.

The Battle of Towton, near Tadcaster, which took place between the Yorkists and the Lancastrians on Palm Sunday 1461 and was the bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil, was marked by such a cross, that still survives, as does the Percy Stone, set up after the Battle of Otterburn in Northumberland, fought on 5 August 1388 between the English and the Scots.

After that the history of war monuments and memorials is remarkably silent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

There are none to the defeat of the Armada – the only survivors of that date appear to be a beacon pyramid at Compton Pike in Warwickshire and a beacon platform at Alderley Edge in Cheshire.

The large Armada monument of Plymouth Hoe dates only from 1888. The Civil War, too, has left few monuments. Most of those that are on battlefield sites are either 19th or 20th century – the Marston Moor obelisk, for example, was unveiled only in 1939.

The Battle of Waterloo, marking the final defeat of Napoleon, might perhaps have provided the impetus for national commemoration, but even for this major event there was little outcome. Scotland did decide to go for a national memorial, on Calton Hill overlooking Edinburgh, at the cost of £42,000. It was to be a replica of the Parthenon.

George IV laid the foundation stone in 1822 – but not enough money was raised, and only one row of columns was erected.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

The Crimean War generated rather more monuments – the main one is in Waterloo Place in London, and depicts three guardsmen and a figure of honour, cast in bronze from cannon captured at Sevastopol.

Another of the Sevastopol cannon once stood in Ripon’s Market Square; it was placed by the obelisk in 1857, moved near to the Cathedral in 1896 and scrapped in World War II.

The Boer War, too, is commemorated in a number of monuments, including a Gothic one near York Minster designed by the architect George Frederick Bodley, with the names of the fallen inscribed on it.

But it’s World War I that has most memorials – and the principal one, the focus of the nation’s tribute every Remembrance Sunday, is another work by Sir Edwin Lutyens – the Cenotaph in Whitehall.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn early July 1919, the Prime Minister, Lloyd George, asked Lutyens to design a central focus for the Peace Day Parade on 19 July. Lloyd George proposed a ‘catafalque’, a raised box of the type to support a coffin, but Lutyens said, ‘Not a catafalque but a cenotaph’ – a Greek term meaning ‘empty tomb’. He did the design – with no fee – the same day, and the new Cenotaph was in place for the event.

It was constructed of wood and plaster, but was so appreciated by the thousands of people who visited it after the parade that the Cabinet decided it should be a permanent memorial. On 23 October 1919, it was announced that ‘a replica exact in every detail in permanent material of present temporary structure’ would be built in Portland stone.

The new permanent structure looked exactly like the temporary one – but it wasn’t. Lutyens did new drawings that reveal some of the Cenotaph’s secrets; first, that what were vertical lines in the original are now very slightly tapering; he notes on his drawing ‘Lines to meet at approx 1,000 feet above ground’.

And there’s another trick – the apparently-horizontal lines are in fact curved; if you extended them they would curve into the earth to form a sphere with a radius of 900 feet. Such refinements he learned from the Greeks – the Parthenon has similar curvature – and help to make the structure seem more substantial when viewed either from afar or up close.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe new Cenotaph was unveiled by King George V on 11 November 1920, during a day that also saw the burying of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey.

Most cities, towns and villages have their own World War I memorials – many later inscribed to the dead of the Second World War, too.

As we approach the centenary of the Great War’s end, we should continue to respect the many monuments that have been erected throughout the ages to everyone who has died in such conflicts.