Nostalgia: The revolutionary birth of the NHS 70 years ago in post-war Harrogate

On July 5, 1948 the National Health Service arrived, the result of the National Health Act of 1946.

Seventy years on it may be hard for some to grasp the revolutionary effect of this service, which provided a safety net for those members of British society in need of medical attention but without the financial means of paying for it privately.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere were certainly alternative means of funding the medical requirements of citizens before the coming of the National Health Service, such as insurance schemes, workers co-operatives, charities of both general and specialized nature, and private philanthropy, but for innumerable people, the inability to pay for vital medical treatment was a fear that the National Health Service removed.

By 1946, Harrogate was still regarded as a wealthy town, although it had a few poor areas destined for clearance and development, primarily at Smithy Hill, Tower Street and Union Street, which had been postponed by the Second World War. For decades, the only means of financing both the Infirmary and the Royal Bath Hospital had been through charitable provision, which meant that the effectiveness of medical provision was often dependant on the effectiveness of fund raising.

After 1948, the new Act meant that the provision of basic medical services were no longer dependant on charity, but could be established and administered on a reliable and regulated basis, which if it did not remove the need for charitable intervention in all cases, at least gave every citizen the comfort of knowing that the British state provided a basic safety net. As for Harrogate Corporation’s Royal Baths, they were a rate-supported enterprise, although since the 1930’s their profit margin had been shrinking, something the unique years of the Second World War had camouflaged.

Harrogate’s own medical practitioners were used to the conditions that had arisen from spa-based private practice, so it might have been thought that they neither welcomed the 1946 Act nor agreed to co-operate with it, but this situation seems never to have arisen. The reason for this was the profound shock Harrogate received in January 1945 with the publication of Professor Davidson’s report into the efficacy of spa treatment. Much criticism came to be levelled against the Professor’s report that – in essence – rubbished traditional spa treatment and opined patients could receive as much benefit by drinking a glass of Birmingham tap water as they could from a glass of Harrogate Mineral Water.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe research had been done in 1944 when the great hotels had been sequestered by the government, and the traditional spa diversions put under wraps. Of Harrogate’s 89 different mineral wells, Davidson had only looked at the water of the Old Sulphur Well, and he ignored such essential spa activities as regulated diet, exercise, water drinking and freedom from stress through entertainment. To the profession who had built their careers by upholding the spa, Professor Davidson seemed to herald the end of a long and glorious era. The arrival of the 1946 National Health Act within a year of the professor’s report may, for some, have seemed a prospect of salvation.

But even before the passing of the 1946 Act, many in Harrogate knew that the post-war world would be very different from the pre-war one. Harrogate, at this period, was fortunate to have Alderman C. Jack Simpson as Chairman of the powerful Wells and Baths Committee that controlled the municipal spa. Alderman Simpson had warned Harrogate as early as December 1942 that it was essential to start planning how Harrogate would fit into the nation’s post-war health services, and from this there grew the concept of the spa becoming a national centre for the treatment and study of rheumatism. This was to be worked up in to a major scheme when the National Health Service arrived.

Apart from Harrogate’s Corporation, the leading players at this time were the members of the powerful Harrogate Medical Society, who sent their patients to the Royal Baths and without whose favourable opinion the Corporation were unwilling to do anything relating to the spa. But the enthusiasm of the Corporation and the town’s medical profession for the Spa had to be tempered by the reality of the financial situation of the times.

During the final year of the war, from 1944 to 1945, income from the total treatments provided at the Royal Baths was £82, 996, whereas during the last full year of peacetime, it had been £89,174. Although this may not have seemed too great a decline, the reality was that there had been a severe reduction in the number of cheaper treatments given. Whereas in 1938-9, the number of treatments by the weekly sulphur water “cure” (three sulphur baths and sulphur water drinking) had been 4,257, by 1944-5 the figure had fallen to 234. The more expensive electrical treatments provided in 1938-9 had numbered 11,914, whereas in 1944-5 they numbered 11,599.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese figures were typical, in that they showed that although the financial basis for the spa was holding its own, this was only because a very few of the more expensive treatments were responsible, the once widely consumed and cheaper treatments being drastically abandoned. As most of the more expensive treatments were for rheumatoid complaints, for example, hot peat packs, electric lamp, Berthe Baths and Paraffin Wax, it was obvious to all that the study and treatment of rheumatism would have to play a significant role in the future of Harrogate’s Municipal Spa.

Harrogate was not alone with regard to the role of rheumatism. In January 1946 the Wells and Baths Committee learned that the British Spas Federation had asked all its members to approach their Members of Parliament to request that spas should be taken in to the new NHS for the study and treatment of rheumatism. Harrogate’s MP, Mr York, represented Harrogate’s interest during the Parliamentary debates which naturally involved Minister Herbert Morrison as Lord President of the council. By April 10, 1948, the Advertiser reported that C Jack Simpson, now Mayor, had been asked by the Minister of Health, Aneurin Bevan, to prepare a scheme for Harrogate to co-operate with the local University (Leeds) for the treatment and study of rheumatism. By the end of the year, Harrogate and the Leeds Regional Hospital Board jointly presented a £500,000 scheme to make Harrogate the biggest centre in the country for research and treatment of rheumatic diseases, the proposals being presented to Mr. Aneurin Bevan during his visit of December 8, 1948.

The scheme called for the Royal Baths to become a rheumatism clinic and treatment centre, the Harlow Manor Hotel in Cold Bath Road to become a research hospital, and the White Hart and Crown Hotels to be converted into annexe hospitals for walking patients. The Royal Bath Hospital in Cornwall Road was to have its capacity increased from 150 to 400 beds. On December 8, 1948, Mr Bevan made a surprise visit to Harrogate to “see for himself” when he was shown the spa by Mayor C Jack Simpson.

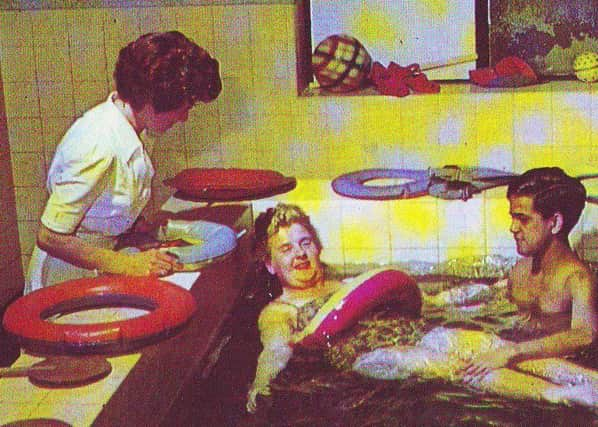

Despite its important role, Rheumatism was not the only ailment to be treated at the Royal Baths. A surviving list of staff in 1953 lists twelve male and twenty-one female treatment staff who were qualified to deliver treatments with diathermy, cataphoresis, Bergonie, massage, paraffin wax, Bertholet, Vichy, peat, hot air, Plombiere, contrast, sulphur, Nauheim, Turkish, fango pack, ultra violet light methods. Many of these staff were highly qualified and long-serving members of the Royal Baths establishment. Since the arrival of the National Health Service, all of these special treatments were available on the British State, one of the most frequently prescribed being the deep pool and Physiotherapy department.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe great £500,000 scheme was never fully implemented, although the co-operation between the Leeds Regional Health Authority became essential to the survival of Harrogate’s spa. The first National Health patients were referred to the Royal Baths from both Harrogate and Ripon Hospitals on March 1, 1949. Those from the Royal Bath Hospital in Cornwall Road following from April 1. This arrangement undoubtedly saved Harrogate’s municipal spa, which closed in 1968 only when the Leeds Regional Hospital Board stopped sending National Health patients to the Royal Baths, by which time a scheming Town Clerk and Council leader had lined up developers whose financial power appeared to outweigh the very real possibility of private patients enabling Harrogate’s 400-year-old spa to survive. But that, as they say, is another story.

l Such is the importance of our nation’s National Health Service that it is necessary to ensure that the recording of its existence is not left to either medical professionals or historians, but that the memories and opinions of the wider public are preserved. With this in mind, the Friends of Harrogate District Hospital are inviting readers to send their memories of the birth and early days of the NHS. Their responses will be incorporated in a booklet being prepared about the National Health Service in Harrogate, extracts from which will eventually be reprinted in this newspaper, should be sent to: nhsturns70@ya hoo.com or posted to NHS Turns 70, Charity Office, HDFT, Harrogate District Hospital, Lancaster Park Road, HX2 7SX.