The Civic Society column with David Winpenny

What is this subordinate but important art? The answer comes in the title of the lecture from which this quotation is taken: ‘The History of Pattern Designing’; his subject is how, over the ages, we have used pattern to enliven a wide variety of surfaces, so that they become more pleasing to the eye.

As far back as we are able to look into pre-history, human beings have decorated flat surfaces. Some of the decorations – for example the cup-and-ring markings and spirals on boulders on remote moorland in places such as Ilkley Moor – may have been of religious significance, but much must have been purely for enjoyment. We need only think about the earthenware drinking and cooking vessels made by the people who took their modern name from them – the Beaker Folk.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBands of impressed decoration on them, made with a fingernail or a stick, demonstrate that humans, alone in the animal kingdom, make patterns for pleasure.

Patterns can be as primitive as those – or extremely complex. Roman mosaic pavements are pattern making. Some are simple geometric patterns, others flow across the floor in a kaleidoscope of figures and animal shapes, even attempting to look three-dimensional.

The most successful are the patterns that respect the single plane of the surface, but which decorate it in an interesting manner.

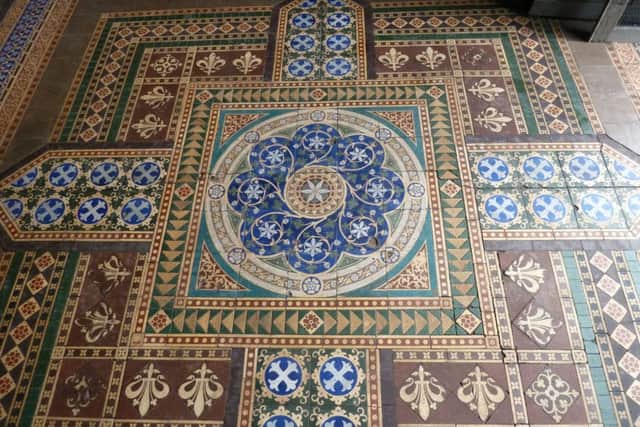

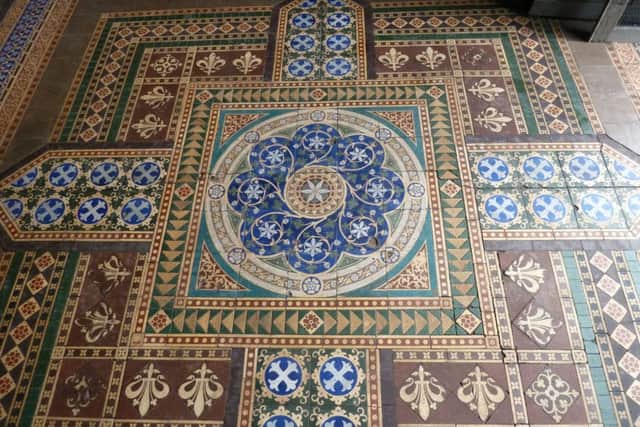

That was something that medieval builders recognised. If we look at the (reconstructed) tile floor on the place where the high altar of Fountains Abbey stood, or the tiles at Byland Abbey that are still in situ, we can see that the designers took delight in making tiles of several shapes that could be fitted together in different patterns. There was no practical need for such complexity; it was done for pleasure and for the glory of God.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd even when they took an easier route (for laying different shapes of tiles requires a sophisticated level of skill), they used square tiles that were inlaid with designs.

Some were simple, such as stars and fleurs-de-lys, but many were designed to produce complex patterns. This fashion was revived in the 19th Century, when firms like Minton and Goodwins produced medieval-style tiles for church restorations throughout Britain; there are spectacular examples of Minton tiles, with portraits of monarchs, in the choir of Lichfield Cathedral, for example, and on a smaller scale in the porch of Pocklington Parish Church.

In the 18th century there was a move to repave the floors of churches; at York Minster, the nave was relaid between 1731 and 1736 in a new pattern designed by William Kent and supervised by Lord Burlington.

The pattern chosen was, perhaps surprisingly for the greatest Gothic cathedral north of the Alps, a classical Greek Key design. It worked well and is still there, mostly unnoticed by the thousands of tourists who walk on it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPattern could also be applied to wall surfaces. Medieval churches had wall paintings of religious scenes (some still survive in Ripon Cathedral) but most would have had all surfaces painted, often in simple rectangular lines representing masonry.

This, also, was occasionally reproduced in Victorian times – there is a fine example, this time in mosaic, in the chapel of St Mary in Castro at Dover Castle.

Sometimes, though, the decoration was not applied as an addition to the wall – it was part of the construction itself.

It might consist of simple diamond-shaped decoration – diaper work – on a wall, as in the eastern part of the interior of Westminster Abbey.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOr, in the Norman period, architects were fond of adding patterns of columns and arches to the walls – patterns that had no structural purpose but were attractive to look at. The inner west wall of Ely Cathedral is a fine example of this style.

Domestic walls were often painted with patterns, too, in the Middle Ages; some boards discovered behind plasterwork at Norton Conyers, painted red, green and white patterns, are typical.

When coal replaced wood as the fuel for domestic premises, wood panelling replaced painting or tapestry, and was also often decorated, for example with ‘linenfold’ carving.

The dictum that patterns must respect the flatness of the surface was gradually ignored, and by Victorian times pattern makers were striving for ever-more-complicated effects; think of elaborate mid-19th Century carpets decorated with life-like roses and vines, trying to look three-dimensional and offering the impression that walking on them was like wading knee-deep through vegetation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s not surprising that William Morris, with whom we began, reacted against such excesses. He looked back to the past as the inspiration for his designs – he was keen on Persian design, and Persian influence can be seen behind the regular patterns and luxuriant geometry of his chintz and wallpaper designs.

Later designers, like Voysey and Heal, built on Morris’s style; then came the swirls of Art Nouveau and the jazzy, jagged style of the Art Deco – again, despite their great differences, respecting the essential flatness of applied pattern. After World War Two there was interest, spurred by the designers at the Festival of Britain, in patterns influenced by science, so we find fabric and wallpapers with patterns looking like atomic models. In the more recent past we have had the dainty, 18th Century style fabrics and wallpapers introduced by Laura Ashley, and the taste for wallpaper with large flowers on a ‘feature wall’ – again, patterns with a geometrical basis and not, usually, trying to be three-dimensional.

And where are we now? There seem to be several schools of thought about pattern. Do you go for the pure geometrical design of triangles or octagons? For the retro-1950s look? For a return to something like the cabbage-rose style of the Victorians, which fashionable designer Cath Kidston has reintroduced? Whatever your style, remember that pattern can say much about your taste – and take care!